Summer 1986—my track record as a writer: one published short story and a completed novel. After months of trolling for an agent by snail-mailing hard-copy packages made up of the first three chapters plus an outline, I had only one bite. “Cut out the first three chapters,” the agent suggested, “then start with chapter four.” I was rewriting furiously, aiming to resubmit before she forgot about me. And amidst all this the same questions nagged me: Am I a writer? Can I consider myself a writer? Can I even say the word in mixed company?

My concern went beyond my thin track record. I had a full-time job as a lawyer. My writing time was confined to my 45 minute Metro North commute between the suburbs and New York City, plus whatever lunch hour I could grab. With such a tight schedule, output was always a top of mind concern. Could I ever rain words down on the page at a rate that would allow me to write the novels I envisioned myself writing?

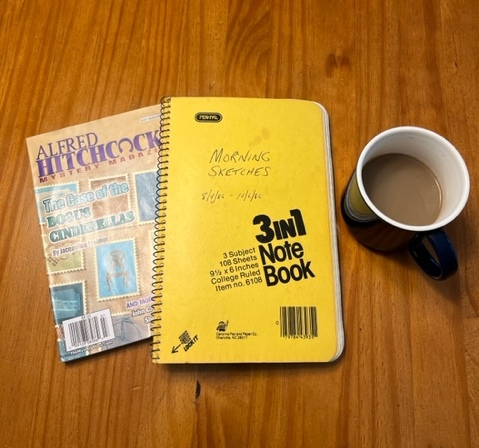

The answer came in the form of a book, Becoming a Writer, by Dorothea Brande. I’d purchased the book a few years earlier from the Quality Paperback Book Club, a choice made hastily to avoid automatically ordering the club’s monthly selection. And there it sat on my bookshelf, its spine unbroken, not even for a cursory browse. In the summer of 1986, I opened it.

The book was not what I’d expected. It mostly ignored the craft of writing and concentrated instead on how to be a writer, or more precisely, how to become a person who can exist as a writer. The chapter titles mixed the nebulous with the practical: What Writers Are Like; Harnessing The Unconscious; Writing On Schedule; and The Critic At Work On Himself. I read the book and found it interesting. But the lasting takeaway came in a section called Toward Effortless Writing. This, I thought, was what I needed.

The advice for achieving effortless writing was very specific: “rise half an hour, or a full hour, earlier than you customarily rise . . . and without talking, without reading the morning’s paper, without picking up the book you laid aside the night before—begin to write.” The subject of this writing was to be anything that came into your head. The goal was to write “rapidly and uncritically” because “the ultimate worth of what you write is of no importance yet.”

I began this practice on August 4, 1986, printing the words “Morning Sketches” on the cover of a 6″ by 9″ college ruled wire notebook. So what came into my head while sitting alone in my quiet kitchen with a cup of coffee at my elbow? As this regimen of daily sketching developed into a habit, the recurring subjects fell into a few broad categories:

—meditations on places where I’d lived

—anecdotes from the courthouse where I worked

—sketches of people I knew or recently met

—childhood memories re-examined with the benefit of adult wisdom

I soon realized that these daily sessions were not only strengthening my writing stamina but also honing my abilities in the four building blocks of fiction. My meditations on familiar places became conscious attempts at creating settings. My courthouse anecdotes blossomed into mini-plots. My sketches of real people trained my eye to look deeply into characters. And my re-examined childhood memories added dialog to create rounded scenes.

I wrote my Morning Sketches for more than three years without missing a day, then for another eight years skipping only weekends and holidays. By 1998, the entries became sporadic. Now they are so rare as to be non-existent. Did my writing ever become effortless? I don’t think so. But I managed to transform all those train rides and many lunch hours into eight published novels and, as of today, 40 published short stories.

The germ for “Italian Alzheimer’s” was a Morning Sketch from August 14, 1997. The entry recounted a discussion about two neighborhood women, each by then deceased, and a suspicious connection that bound them together. It was this connection — a vague story involving the unsolved murder of a NYC taxi driver who may have dated both women simultaneously in the late 1940s—that piqued my interest enough to explore in a story.

Morning Sketch entries have suggested other stories in my personal bibliography: “The American Professor” (AHMM Nov. 2011); “The Visit” (EQMM Sept./Oct. 2019); “Escape Velocity” (EQMM Mar./April 2021); and “Becoming Ian Fleming” (AHMM Sept./Oct. 2022).

Those spiral notebooks (18 of them with 108 pages in each, written on both sides) sit on a bookshelf in my basement. An incomplete index, which I attempted to create in the mid-1990s, offers some guidance. But lately, I’ve been pulling down a notebook at random and diving in. I find myself continually surprised at the neatness of my penmanship and the clarity of my writing. More importantly, I turn each page with the possibility of finding the seed for my next story.