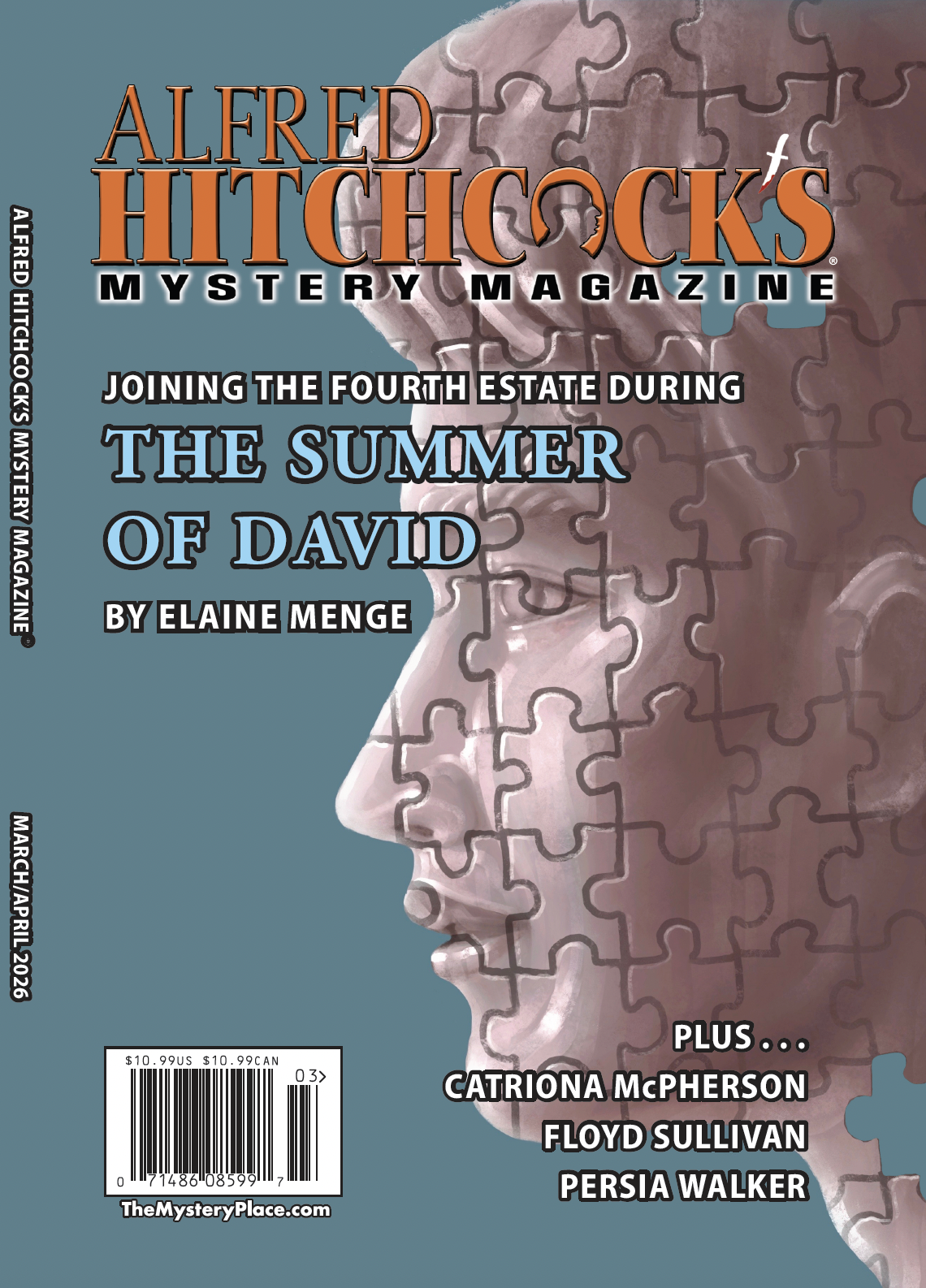

Floyd Sullivan shares how memories of working with his father in construction contracting inspired his latest story, “Murder on the Job,” from our March/April issue, on sale now!

As has often been said, and written about by other writers, many of whom have contributed to this blog, one never knows when the inspiration for a story will present itself. In the case of my most recent mystery published in Alfred Hitchock’s Mystery Magazine (AHMM), the idea came in the form of a memory long tucked away in a back corner of my consciousness, something said to me, almost in passing, by a fellow employee as we rode in the front cabin of a battered old truck through the North Side of Chicago over fifty years ago.

During the late 1950s my father worked as an engineer for a construction contractor. He “figured” and supervised projects that included the installation of large underground storage tanks and the piping and pumps those tanks fed. It was a good job, but he wanted to run his own show. An opportunity arose when the owner of a similar company suddenly died and his widow wanted to sell the business rather than run it. A friend loaned my father the capital, and thus was born Sullivan Tank Service.

Summers during my high school years, as soon as I was old enough to use a long-handled shovel without hurting myself, I would help out by digging trenches and spreading sand and pea gravel over buried tanks. It was hard, sometimes brutal, work, but my father paid me well and the intense exercise kept me in shape. Over the years, through college and after, I graduated to simple pipefitting tasks.

My father had moved into the previous owner’s office on the far north side of Chicago, but soon realized he could work from a “home office,” before the term was popular, save on monthly rent, and claim a deduction on his income tax. And because his office was in our house, he had ready help available in the persons of his eight children. I took a typing class in high school, ostensibly to help me more quickly execute term papers, but my new skill also made me a very convenient office resource, my bedroom only a few yards from my father’s desk and typewriter. Thus would I be recruited (a “handcuffed” volunteer, as my father put it) to type invoices and job proposals, usually addressed to general building contractors, or engineers from the major oil companies. Most of our contracts involved installing underground tanks, piping, and pumps for gas stations.

These experiences, and the settings of my father’s office and various job sites, informed the details of my latest Rick Peters story, “Murder on the Job,” published in the March/April 2026 issue of AHMM. The inspiration for the crime itself came one evening when the company’s pipe-fitter, and informal foreman, named Louis, drove me home from a job site. We rode in his truck south on a main thoroughfare toward Oak Park, the Chicago suburb where I lived. I was exhausted, achy, sweaty, and covered with gas station grease, dirt, and caked glops of clay, but grateful to be on my way home. As we waited at a red light about five miles north of my house, Louis gestured to a line of nicely maintained yellow brick homes along a shady, tree-lined street and told me that the former owner of the company lived on that block.

And then he told me how he died.

To relate to you exactly what Louis said that evening would spoil a dramatic (I hope) passage of the story, so please pick up a copy of AHMM March April 2026 and read “Murder on the Job,” as well as the other excellent mysteries in the issue. Another bonus is you’ll learn how a very young Rick Peters got involved in his very first mystery. And you’ll meet his high school girlfriend Maxine, a character I plan to bring back in future Rick Peters stories.

I hope you enjoy my story and its settings, full of pipe wrenches and long-handled shovels and huge storage tanks and heavy earth-moving machinery. In the meantime, I’m digging back into those buried memories from decades ago, hoping to uncover another inspiration.