Linda Mannheim is the author of works such as Above Sugar Hill and Noir. Her short stories have appeared in 3:AM Magazine, Ambit, New York Stories and New Contrast. She was a visiting associate at the Centre for African Studies at the University of Cape Town, and here she discusses the research and source materials for her revealing and unique story “Documents” in the current issue of the magazine.

I was up to my elbows in archival material when I found the note, handwritten on a scrap of paper:

There’s a little surprise carefully concealed in a Click’s carrier bag in the fridge for little Ekraam (who speaks so well on the phone) who could be forgiven for not being circumcised before he knew the way to heaven (so long as you don’t mention the word Palestine). So…. Es mein kindt. Forward the people’s struggle (on chicken bones and gefilte fish)!

I couldn’t stop thinking about the note, wondering who it was written by, who it was left for, what their story was.

The archives belonged to the University of Cape Town library’s special collections. I was visiting from the US, having pitched my project as “research for a collection of unconventional war stories.” Almost ten years after the end of South Africa’s apartheid era, when it was spring in the Southern hemisphere and autumn back home, I was trying to solve a mystery of my own. How had the white minority government stayed in power for so long? What was the apparatus that they’d used to divide, rule, and remove people from their homes?

The answer was in those archives—in the legal documents, political pamphlets, and handwritten letters in those boxes. In 2003, much of the material was still uncatalogued, so when I opened each box and examined the documents on the long tables in the whispery special collections room, I didn’t always know what I would find.

I photocopied some of those documents, and the copies are spread before me again now: a notice informing a property owner that their town had been declared a “a White area” and as they were not white, they would have to sell their property and “settle in their own area”; a pamphlet from an activist advising residents of “mixed race areas” of what to do when police came calling to harass residents; a notice of appeal to authorities who had undervalued the home of a family forced to leave an area that had been “declared White.”

The minutiae of apartheid, the documents used to control people’s lives, fascinated me. Every American of my generation (who came of age in the 1980s) knew about whites only areas, the shanty towns where black South Africans were forced to live, the banning of anti-apartheid political activists and the brutality of the pro-apartheid police. But the depth of that brutality, the reach of the apartheid government’s control, became clearer to me when I looked at official documents—in the decrees and the laws that dictated the movements of people’s day-to-day lives.

I was also riveted by the documents from the anti-apartheid activists and one group of documents in particular seemed so familiar to me—I kept imagining the person who they’d belonged to. There were letters to universities in Britain from an activist who had to flee South Africa, budgets worked out in sterling and in rand, notes from meetings to encourage disinvestment in apartheid South Africa. And then, in the margin of a page of notes, an aside written in bubbly ornate lettering: “This is a wonderful pen!”

It was easy to wonder who the activist was, who his family was. The note about the treat in the fridge (in a carrier bag from a discount drugstore chain) had to be from a mother-in-law, and the mother-in-law was clearly Jewish. The child was not named Ekraam, but his name made it clear that some of the family members would have been designated white in apartheid South Africa and others non-white, which in and of itself would have been illegal during that time. I wanted to tell the story of the imaginary family by incorporating some of the documents from the archives as well as through a fictional set of notes and letters.

After I’d written the first draft of “Documents,” I found out more about the person whose papers had inspired the story. His story, and the story of his family, was not the story I told in “Documents.” I was happy to find out that he and his family were well, though. He hadn’t even realised his papers from the 1980s were in the archives, but he graciously gave permission to use to segments that are verbatim.

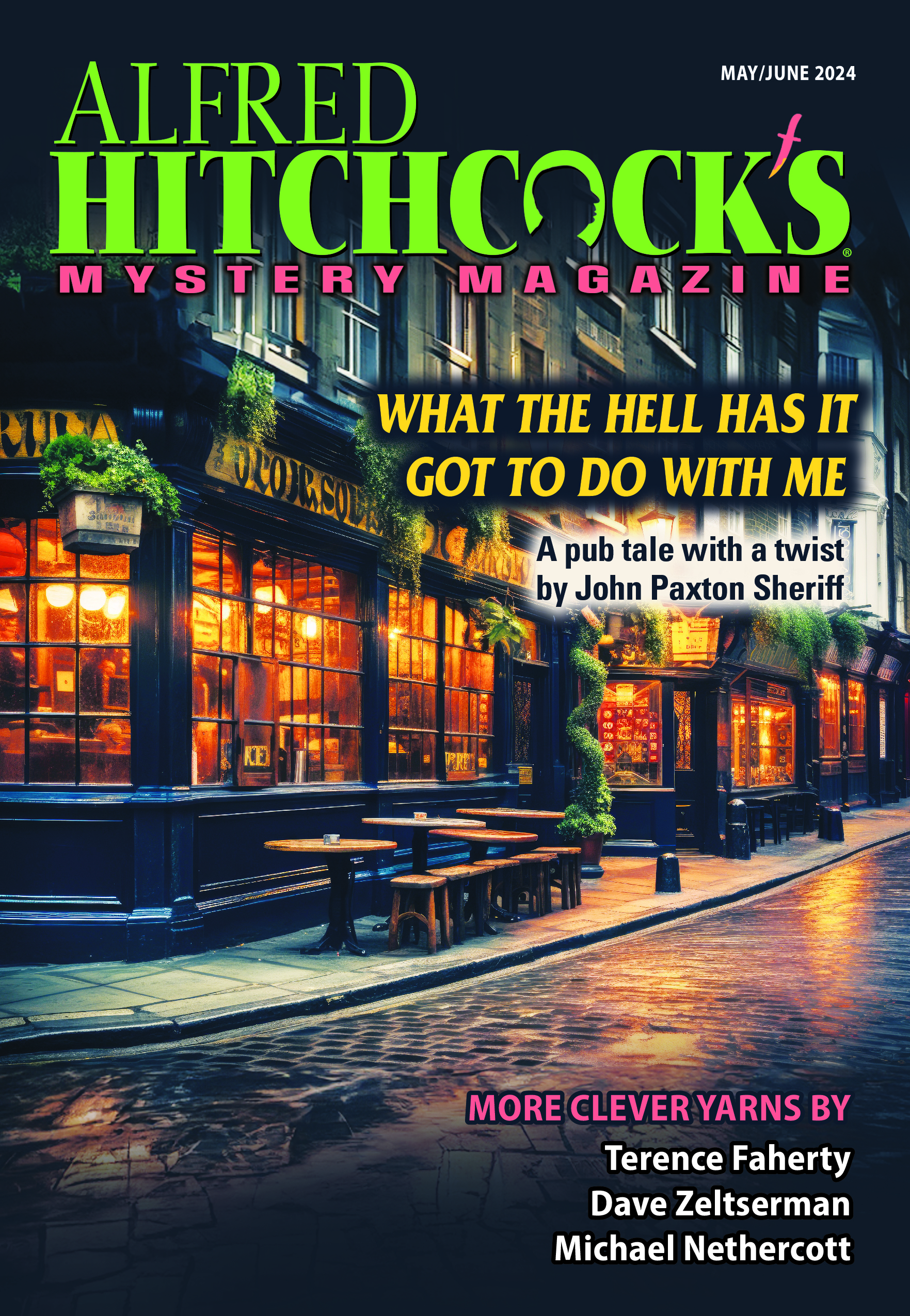

I love that Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, in guidelines for writers, asks “only that a story be about a crime (or the threat or fear of one).” The most compelling mysteries, to me, are ones where the crime is carried out by the state or other official bodies and the protagonist has to break laws to cope with that crime. I’m a sucker for the kind of Noir tales where a private eye confronts crooked cops. I’m interested in 1970s muckrakers uncovering city corruption. And South Africa in the 1980s too, was a place where individuals had to use subterfuge to survive a brutal and corrupt system.

Nearly all of the stories that I pitched as “unconventional war stories” when I went to South Africa turned out to be mysteries in the end. Nearly all were about people who became fugitives or victims when the law turned against them. Nearly all had to break those laws to challenge injustice.